Effects of seismic operations on bowhead whale behavior:

Implications for distribution and abundance assessments

Research Background

Understanding how animals respond to human activities is vital for developing appropriate and effective conservation and management policies. Studying animal behavior allows us to gain insight into how animals respond to various human activities and what the consequences of such responses may be.

Arctic marine systems are experiencing rapid changes in ice cover and human activities. In the Western Arctic bowhead whales (Balaena mysticetus) are exposed to a variety of human activities resulting in a growing demand for effective management and mitigation strategies that will ensure minimal disturbance to the whales and the Alaskan Iñupiat whale hunt.

A good understanding of the distribution and abundance of bowhead whales in relation to human activities, e.g., seismic operations, are key components of conservation and management strategies designed to minimize the effects of human activities on wildlife populations and subsistence harvests.

Arctic marine systems are experiencing rapid changes in ice cover and human activities. In the Western Arctic bowhead whales (Balaena mysticetus) are exposed to a variety of human activities resulting in a growing demand for effective management and mitigation strategies that will ensure minimal disturbance to the whales and the Alaskan Iñupiat whale hunt.

A good understanding of the distribution and abundance of bowhead whales in relation to human activities, e.g., seismic operations, are key components of conservation and management strategies designed to minimize the effects of human activities on wildlife populations and subsistence harvests.

|

My research aimed to address concerns surrounding the potential impacts of seismic survey operations on bowhead whales in the Alaskan Beaufort Sea. I used behavioral data collected in the Beaufort Sea from 1980-2000 to investigate the effects of seismic operations on the behavior of bowhead whales. I was able to determine that whales changed their surfacing, respiration and dive behavior in the presence of seismic operations and that these behavioral changes were context dependent (i.e., they were contingent on the whale’s circumstance and activity).

To determine the influence of behavioral changes on the sightability of whales to aerial observers I estimated and compared sightability correction factors specific to whales exposed and not exposed to seismic operations and found that whales in all circumstances were less available for detection when exposed to seismic sounds. In particular, non-calves were the least available to observers during autumn when exposed to seismic activities, regardless of activity state. Using a combined line-transect distance sampling and spatial modeling approach I was able to generate corrected density estimates for bowhead whales in an area of the southern Alaskan Beaufort Sea ensonified by seismic operations between late August and early October 2008. This approach allowed me to investigate the extent to which density analyses were affected by changes in whale availability. This work revealed a wide-spread nearshore distribution of whales within the ensonified area with some spatial segregation related to activity state. Density estimates that accounted for variations in whale behavior due to seismic operations were also 3-68 % higher than previous estimates. Collectively, these findings suggest that seismic activities may not have displaced bowhead whales as previously thought, but altered their dive behaviors instead ,making them less visible for counting. My research demonstrated the importance of accounting for behavioral reactions when assessing impacts of seismic operations on distributions and abundances of whales. All of my analyses have been completed in R and Distance. |

Download PhD Thesis here:

| ||||||||

Research posters

The bowhead whale Balaena mysticetus - Agviq

Photo: Paul Nicklen

The bowhead whale Balaena mysticetus

has a circumpolar distribution in the northern hemisphere. The Bering-Chukchi-Beaufort

(BCB) population is the largest. Once numbering between 10,000 and 23,000

animals (Woodby and Botkin 1993), the BCB population was probably reduced to

less than 3000 animals by heavy commercial exploitation in the mid‑ to late

19th Century.

This population is listed as endangered under the US Endangered Species Act, as a species ‘of special concern’ in Canada (COSEWIC 2005), and as 'least concern' by the IUCN Red List. The 2011 population estimate 16,892 (95% CI 15,704-18,928) (Givens et al. 2013), and suggests that this population is recovering, despite an annual subsistence harvest and exposure to other human activities across its range. However, concerns surrounding cumulative impacts from human activities remain.

This population is listed as endangered under the US Endangered Species Act, as a species ‘of special concern’ in Canada (COSEWIC 2005), and as 'least concern' by the IUCN Red List. The 2011 population estimate 16,892 (95% CI 15,704-18,928) (Givens et al. 2013), and suggests that this population is recovering, despite an annual subsistence harvest and exposure to other human activities across its range. However, concerns surrounding cumulative impacts from human activities remain.

A brief natural history of the BCB population of bowhead whales

|

The bowhead whale is a member of the right whale family and is the only baleen whale to remain in Arctic and subartic waters year round. Bowhead whale habitat ranges from open water conditions to extensive pack ice and as a result bowheads are well adapted to heavy ice conditions. Bowheads are characterized by their giant bow-shaped head which enables them to break through ice up to 2 m thick. Other adaptations include extremely thick blubber layers and complex acoustic abilities. There is evidence to suggest that whales use acoustics to navigate between ice leads under large ice-flows.

|

Bowhead whales are extremely long lived; new molecular techniques are indicating that these animals live > 200 years. They are also late to reach sexual maturity, as might be expected in such a long lived animal. Bowhead whales mature between 20 and 25 years of age; late maturity and long life-spans are further adaptations to the harsh environment that they inhabit. Bowhead whales calve every 3-4 years. Calves are around 4 m at birth but double in size within the first year.

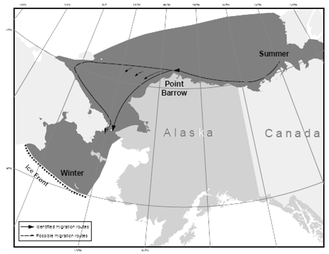

The BCB population of bowhead whales winter in the Bering Sea and migrate in the spring to feeding areas in the Eastern Beaufort Sea and Amundsen Gulf, returning to the Bering again in the autumn. These annual migrations occur in pulses and there is spatial and temporal segregation among age groups. In the summer and autumn distribution is also segregated by activity states, sea-ice conditions and depth . There appears to be a preference for nearshore shallow-water habitat during low-ice years and a preference for deeper water during high-ice years (Moore & Laidre 2006). However, this may reflect a more extensive use of nearshore waters by feeding subadult whales during years with low ice cover and a more extensive use of offshore habitats by adult whales in high ice years (Koski & Miller 2009). Overall, subadult whales seem to prefer shallow nearshore habitat, while larger subadults and adults prefer deeper offshore waters. |

|

Spatial and temporal habitat segregation by age class has been linked to variation in activity states, particularly feeding (Richardson & Thomson [eds.] 2002). Bowhead whales mostly feed on copepods and euphausiids. Three different feeding strategies have been observed during the late summer and early autumn in the Beaufort Sea including water-column feeding, feeding at or near the bottom, and skim feeding near the surface (Würsig et al. 1984). The choice of feeding activity is likely related to prey type, distribution in the water column, density of prey patches and the physiological capabilities of the whale.

|

The bowhead whale and Arctic CultureThe bowhead whale is central to the Alaskan Iñupiat

culture. The importance of the whale dates back to before 1000 AD when the

Thule culture arose in Alaska. The rapid expansion of the Thule across

the Arctic was driven by the movements of and migrations of the bowhead

whale. The Thule was a society based on the hunting of large marine mammals;

activities that demanded cooperation and sharing within the community.

This allowed larger more stable communities to successfully exist in the harsh

Arctic environment. The bowhead whale was able to provide not only food

but also bones for building materials, oil for lamps and baleen.

|

The Thule tradition introduced innovations that allowed for successful habitation of the Arctic, and these traditions were, for the most part, based on the hunting of large marine mammals. The core of modern Iñupiat culture remains the same as their Thule ancestors and the bowhead whale continues to hold great importance. Activities related to the bowhead subsistence hunts occur year round and include the preparation of boats and other gear, community potlucks and celebrations.

A brief history of industry activities in the Western Arctic.

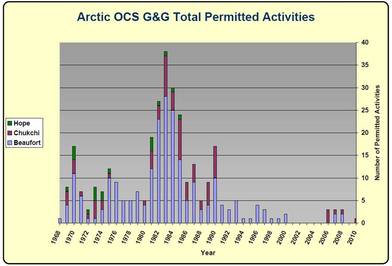

The oil and gas industry has been active in the Arctic since the 1960s. Drilling for oil on Alaska's North Slope first occurred in 1967 and led to the discovery of Prudhoe Bay, the largest oil field in the US at that time. For over 20 years North Slope oil has contributed 20% of domestic production in the US. Exploration of offshore areas began shortly after with marine seismic surveys starting in the early 1970s. The peak of marine exploration occurred in the mid 1980s with most interest focused on the Beaufort Sea. The first well was drilled in 1981 and by the end of the decade a further 19 wells had been drilled in the Beaufort. By 2003 another 10 wells had been drilled, but of all the wells drilled only a few were further developed. Drilling mostly occurred from man-made gravel islands, but drill-ships and ice-islands were also used. Interest in the offshore areas of both the Beaufort and Chukchi Seas picked up again in the 2000's with exploration and development in offshore leases in the Beaufort and Chukchi Seas. In 2012 Shell Offshore Inc. began a drilling program in the Beaufort and Chukchi seas, however Shell pulled out of the Arctic in 2015.

|

|

I used the following sources for the information on this page

For information on bowhead whales try these sites |

Marine Mammal Observers

Marine Mammal Observers (MMOs) and Passive Acoustic Monitoring (PAM) operators are vital elements to mitigation and monitoring programs that are developed to minimize the impact of man-made noise on marine mammals and in some areas sea turtles. MMOs and PAM operators are predominantly vessel based, however in some areas, such as the Arctic MMOs may also be part of an aerial observation crew.

The role of the MMO and PAM operator is to be present on the ships during offshore operations and to act immediately to protect marine mammals should they enter an exclusion zone prior to and sometimes during operations. MMOs will advise personnel on-board to delay or shut-down operations until the animals are at a safe distance and also to record behavior and sightings at other times. Monitoring and management measures may be set out by a responsible authority or follow industry best practice. The MMO will work with the client and contractor to ensure requirements are adhered to and provide clarification advice.

Projects requiring MMOs and PAM operators have arisen due to concerns regarding the levels of man-made noise in the ocean and how this may affect marine life, in particular, marine mammals and turtles.

The four main operations at sea that are causing concern are:

I have sourced this material from the Marine Mammal Observer Association, if you are interested in becoming an MMO, already are an MMO or you are interested in what this association is please visit the web site and don't hesitate to contact the MMOA at:

[email protected]

The role of the MMO and PAM operator is to be present on the ships during offshore operations and to act immediately to protect marine mammals should they enter an exclusion zone prior to and sometimes during operations. MMOs will advise personnel on-board to delay or shut-down operations until the animals are at a safe distance and also to record behavior and sightings at other times. Monitoring and management measures may be set out by a responsible authority or follow industry best practice. The MMO will work with the client and contractor to ensure requirements are adhered to and provide clarification advice.

Projects requiring MMOs and PAM operators have arisen due to concerns regarding the levels of man-made noise in the ocean and how this may affect marine life, in particular, marine mammals and turtles.

The four main operations at sea that are causing concern are:

- Seismic Surveys - looking for new oil and gas reserves

- Explosives - used in the decommissioning of oil platforms and structures

- Pile Driving for Construction – for example wind farm construction, tidal turbine and new piers

- Military Sonar used to detect submarines

I have sourced this material from the Marine Mammal Observer Association, if you are interested in becoming an MMO, already are an MMO or you are interested in what this association is please visit the web site and don't hesitate to contact the MMOA at:

[email protected]