Southern resident killer whale J1. F.C. Robertson

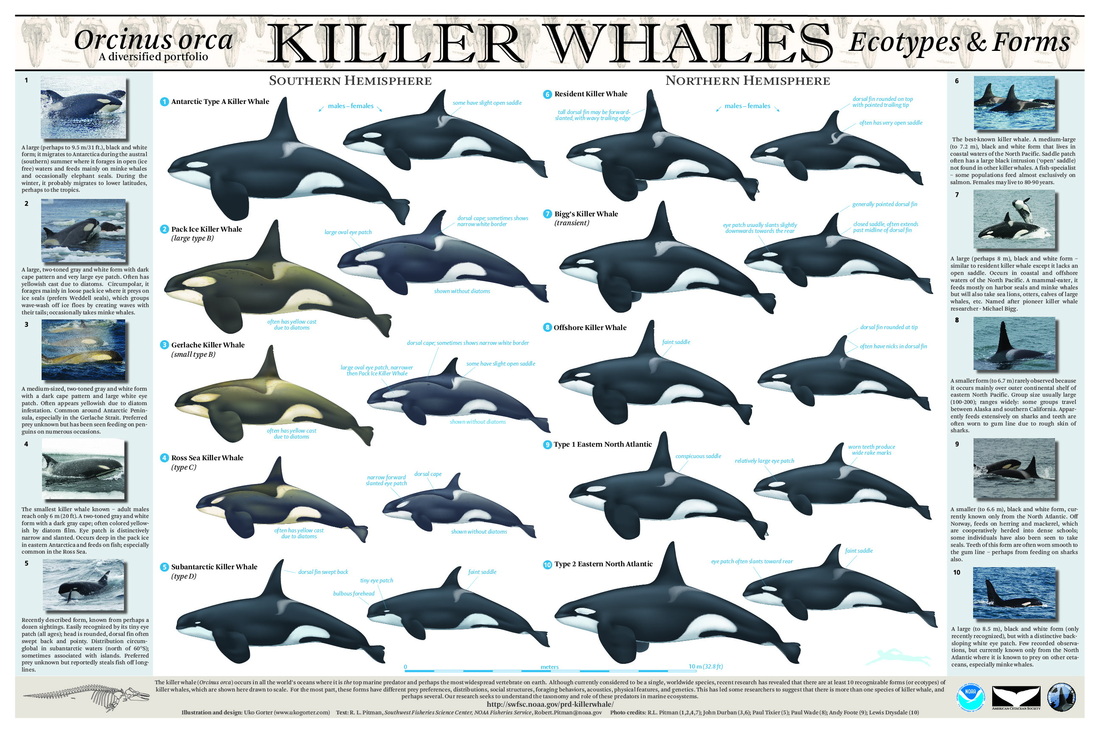

Southern resident killer whale J1. F.C. Robertson Killer whales, described as one of the most cosmopolitan species after humans occur all over the world from the poles to the tropics. Genetic studies are now revealing that there are in fact many different species of killer whale, differences that are often reflected in their morphology, behaviour, prey preferences, and culture. Indeed three distinct types of killer whales occur right here in British Columbia –the resident whales that eat fish, the transients who prey on marine mammals and offshore whales that are thought to prey on sharks.

Just as the types of killer whales vary around the world so do our attitudes to killer whales. My personal attitude to killer whales is one of awe, not because they are big beautiful black and white charismatic whales, but instead because these whales are apex predators. They are the only whale to have evolved to take on the largest animal that has ever lived –the blue whale, or to successfully attack other apex predators such as the great white shark. And to add to this they are also incredibly good at learning how to adapt –for example, in Norway the herring boats used to follow the whales to find their target fish; now the whales follow the boats. Why expend the energy searching for prey if there is a handy group of humans to show you? This ability to learn has inevitably led to conflicts between fishermen and whales.

| In the Arctic attitudes toward killer whales vary greatly. Killer whales generally steer clear of areas with heavy ice cover –they are not well adapted to it with their tall dorsal fins. But as the ice melts in the summer they follow their prey north, retreating again in the autmun as the ice returns. However, with ice-free waters lasting longer killer whales have been able to venture further north for longer periods. In fact over the last decade or so a group of killer whales have taken up residence in Hudson Bay. And in January 2013 a group of 12 killer whales became trapped in the ice after a sudden freeze up –open water had lasted into January and the whales had stayed too long. There was huge outcry to save these whales –people were sending letters to the Canadian government demanding that they send icebreakers to free the whales. Some even suggested dropping boulders from planes to break the ice! I followed the news reports and social media posts with interest. I was well aware that whales sometimes get stuck in ice –even those whales that are adapted to living in this extreme environment such as narwhals and beluga. If the ice does not shift in time to open up channels to freedom the whales drown. While entrapments have been seemingly rare there are some thoughts that these events may be increasing in frequency as the Arctic environment changes. |

As I wrote at the start here in the Pacific Northwest people generally love killer whales (yes I realise that this is a bit of an over generalization but...) –and there is a thriving whale watch industry. But in places where whales are snatching fish of lines they are not looked on quite so fondly. In the Eastern Arctic, just as in other parts of the world, attitudes toward killer whales varies. This morning I finally got around to reading a paper that I have been carrying around for weeks. This paper, entitled “Attitudes of Nunavut Inuit toward killer whales (Orcinus orca) by Kristen Westdal, Jeff Higdon and Steve Ferguson (published in the journal Arctic, 66(3): 297-290) was in fact what led to this blog post. The authors of the paper conducted semi-structured interviews with mostly Inuit hunters and Elders across two regions of Nunavut –Qikiqtaaluk (Baffin Island and Foxe Basin) and Kivalliq (western Hudson Bay).

The point of this paper was to gain baseline data on the attitudes and perceptions of killer whales to help inform future wildlife management decisions in Nunavut. This kind of information is particularly important in the face of possible wildlife management conflicts related to Inuit subsistence harvests of species that are preferred by both humans and killer whales. In reading this paper I was reminded that it was not so long ago that killer whales were feared and disliked. Here on the west coast of North America killer whales have held both great cultural significance, particularly to BC`s First Nation peoples and the Coast Salish people as well being feared and disliked for perceived competition with fishermen. But on this latter point attitudes towards the killer whale have changed from one of fear to admiration. So I think that it is important for us to realize and try to understand that our attitudes of awe and admiration may be a little different to those of other communities, and that it is important to consider these attitudes and perceptions when considering management and conservation of marine systems, whether those attitudes are related to tourism and conservation here in Vancouver or related to how the killer whale might be impacting subsistence harvests in Nunavut.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed