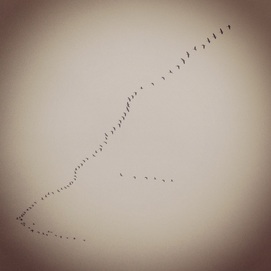

The very V behaviours of birds and bowheads

The distinctive V-formation is known in a number of bird species and has been the subject of interest and intrigue to scientists and non-scientists alike. A team of researchers from the UK’s Royal Veterinary College travelled to Austria to work with the conservation group Waldrappteam – who work with the Northern Bald Ibis, a highly endangered migratory bird that went extinct in central Europe 300 years ago. Waldrappteam rear these birds and teach them to fly and eventually migrate. This is where one of my favourite wildlife themed movies pops to my mind –yep, you guessed it ‘Fly Away Home’. Guaranteed if I am looking after kids I will make them watch it –and I just admitted that here in public....

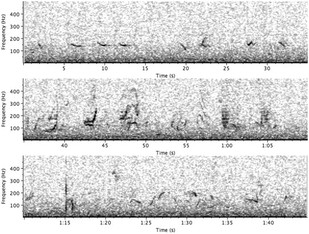

| So the birds are taught to fly and then to migrate by following a microtlite (exactly as it was in the movie). This real-life human led migration has been the first successful one of its kind and has opened up all sorts of great opportunities to study birds in their natural flight –something that was too good an opportunity to pass on for the team from Royal Veterinary College. This opportunity to study the birds’ migratory flight behaviours allowed the research team to investigate why these birds would adopt the V-formation during migrations. |

The team discovered that these birds appeared to have keen awareness of the air structures created by their nearby flock-mates, and even more remarkable was that the birds seemed to have an ability to predict or sense the surrounding air patterns and so how to exploit them to their own advantage.

Source: Nature

Source: Nature

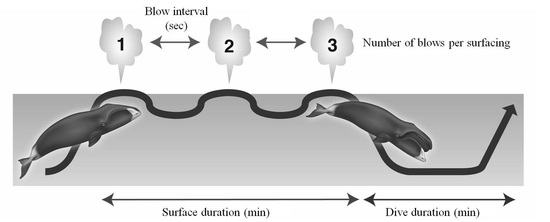

This type of behaviour has also been observed in surface feeding southern right whales. The whales’ adoption of the V-formation ultimately increases their foraging efficiency while at the same time saving energy by drafting behind the lead whale so reducing the cost of swimming, just as the birds exploit the V-formation to exploit the upwash of the bird ahead to save energy during their migrations. So as an energy saving adaptation the V-formation is Very much a winner!

Portugal, S.J., T.Y. Hubel, J. Fritz, S. Heese, D. Trobe, B. Voelkl, S. Hailes, A.M. Wilson & J.R. Usherwood. 2014.

Upwash exploitation and downwash avoidance by flap phasing in ibis formation flight. Nature 505: 399-402

Waldrappteam http://www.waldrappteam.at/waldrappteam/indexl_en.htm

Würsig B, Dorsey EM, Fraker MA, Payne RS, Richardson WJ (1985) Behavior of bowhead whales, Balaena mysticetus, summering in the Beaufort Sea: A description. Fish Bull 83:357-377

Fish, F.E., K.T. Goetz, D.J. Rugh, & L. Vate Brattström. 2012. Hydrodynamic patterns associated with echelon formation swimming by feeding bowhead whales (Balaena mysticetus). Marine Mammal Science. 29(4): E498-507

RSS Feed

RSS Feed