Do something decadent.

This was one of Jon Stern’s things, when you saw those words you knew he was saying them with a flourish in his softly spoken voice and a twinkle in his eye. This is the one thing that I will miss the most today, but regardless I will go out and do something decadent as he would have instructed me to do.

| Last week, on the 16 February 2017, we lost Dr. Jonathan Stern at the grand young age of only 62. It was far too soon and has left a gaping void in the many who knew him, including myself. Jon was a friend to more than I know, he was a respected scientist, a gifted teacher, an influential mentor, and a talented musician with both an appreciation for good music and beautiful guitars. To some he was all these things and more, to others he was a friend or a teacher. But regardless of what one’s connection to Jon was it will leave a profound mark for many years to come. Jon was not only a gifted scientist he was also a man of great class, a gentle man with a generosity to share his knowledge, his love of good food, and his love of music. Such traits are rare to come by these days, but they are what attracted so many to him. I cannot begin to write all that Jon was to those who knew him as everyone has their own memories, stories, and experiences. However, I would like to share a little of my experiences and in so doing share his contributions to the world of marine mammal science, particularly the minke whale. |

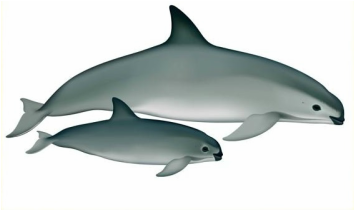

A champion of the minke whale

Into the field with a Lévy flier

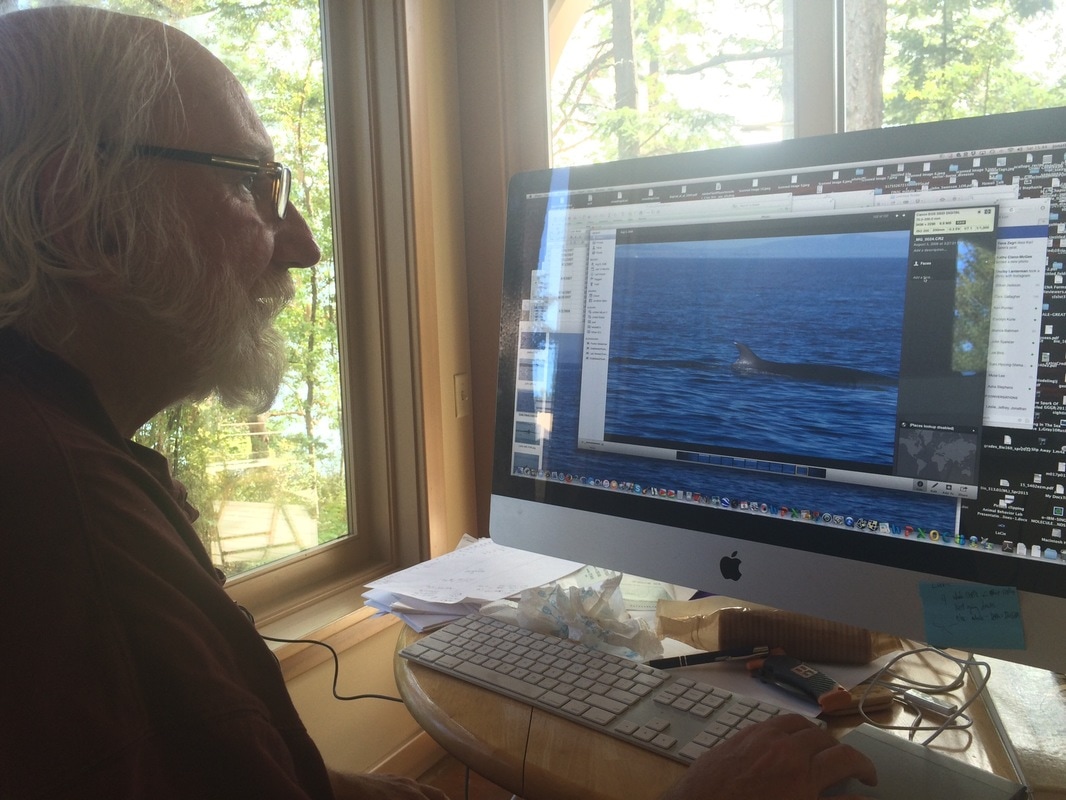

I soon found myself taken onboard as an enthusiastic volunteer, eager to learn what I could. I am not sure what led to us becoming long-term colleagues and friends. I couldn’t code, I am not mathematically gifted, ecology modeling does not come easily to me, and I couldn’t really drive a boat. But regardless of this he let me stick around. Jon addressed my lack of boat driving skills right away, one of my first memories was being ordered into the drivers’ seat of the labs’ motorboat.

He proceeded to teach me how to maneuver through areas with strong currents, ‘always skirt around the flat areas’ he would tell me; ‘those areas are characteristic of upwelling and we don’t want to run into a deadhead’. He taught me how to navigate through the chop of waves so that the ride was smoother, and importantly he taught me how to maneuver around minke whales. Anyone who has spent any time with these elusive whales knows that this is no easy task.

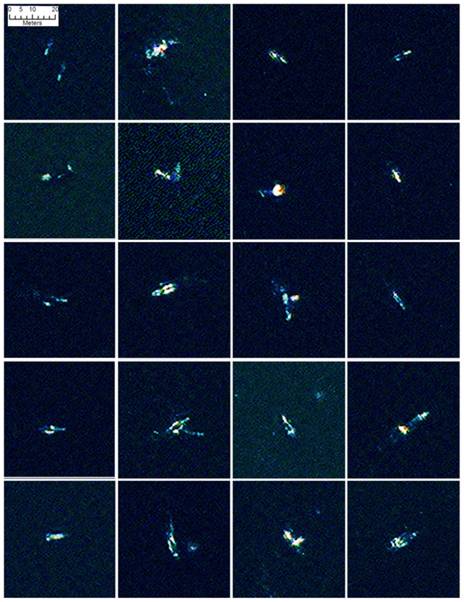

It didn’t take long before I was hooked on the project, captivated by the discussions that we would have surrounding minke whale ecology, movement patterns, the concept of random walks and Lévy flights in relation to the foraging behaviour of minke whales. Essentially through our ability to track individual minke whales Jon was able to analyze the movement patterns of the whales in the context of optimal search strategies. Minke whales appeared to maximize the number of sites with potential feeding patches they were able to visit by adopting a Lévy flight search strategy.

Though not always able to wrap my head around the models Jon had a way to explaining these complex theories and models that allowed one to enter into his world. To then witness the whales’ search patterns was all the more special.

Only a full frame will do

How to research in styleJon knew how to do research in style, if not a somewhat unconventional style. One year our research flag was a skull and cross bones, another year a yellow duster attached to a tiki torch. Clad in his oversized red t-shirt, earing dangling from one year, and red bandana wrapped around an often burned head he certainly fitted the description his friend Doug Chadwick had given him -a cross between a retired rock star and a pirate. He lived up to that description well, never arriving on the island without at least 2 guitars in tow. We never left the dock without a packet of Mint Milanos. At the first sight of a white-cap he would announce that it was time for crab cakes and fluffy ducks and we were beetling back to the dock. Other times, if it was too rough out on the banks we would head off for a tour of the islands ‘on the search for minkes’ though often debating the best and worst of the houses that dotted the west side of San Juan Island. We seemed to only suffer boat breakdowns on the last day of field work, finding ourselves stuck in the shipping lanes between Salmon Bank and Hein Bank was perhaps the most memorable, and occasionally we would find ourselves having to come to the rescue of others. Jon had a deep respect for the ocean and knew when, and when not to push his luck (I suspect, based on the stories of his days chasing minkes off the California coast, that he had experienced his share of lucky escapes), so he was not impressed by those who did not hold the same respect for boating and the seas. Over the years, we were stopped by almost every form of enforcement on the water. He always complimented the size of their engines, and never once asked why we had been stopped -a good lesson for anyone that spends any time on the water here! There were hectic times in the boat as we raced to keep up with a whale, and there were slow times when all the whales seemed to just disappear. During these times, bobbing about out on Hein Bank we dreamed up stories of Bristles (the killer minke), another time it would be something like this: We would be laughing so hard the tears the streaming. |

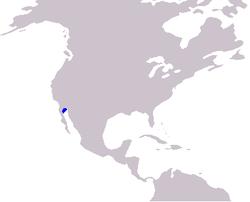

Further afieldOn occasion I would visit Jon in his home state of California. He drove north to Bodega Bay and Point Reyes (always stopping for the best pie in Sonoma County on the way). He drove me south to Santa Cruz and Monterey Bay. Here, he once sent me out whale watching with hope that I might see fin or blue whales. I saw only killer whales while Jon enjoyed a couple of humpbacks lunge feeding near shore. Typical! He made me come out to Hawaii one time to see the humpbacks off Maui. He did these things because he believed that I needed to see and experience these places to better understand the creatures that we studied. Jon always made sure to introduce me to other scientists and friends, people who were also important in his life. I will be forever grateful for this opportunity to expand my networks and sometimes also lasting friendships with individuals who I would never otherwise have had the fortune to meet. |

The last days of data

I only hope I can live up to Jon’s standards in naming future whales. I hope to continue Jon’s work here in the San Juans. My first goals are to publish the papers that we had planned together along with a photo-id guide. Jon’s long-time minke co-investigator here Dr. Rus Hoelzel also plans to publish the papers that he Jon had been working on. In this way we can ensure Jon’s legacy as the world’s leading minke whale expert. Our continuation of Jon’s life’s work is the best tribute that we can give to this gifted, generous, and incredible scientist and friend that we are going to truly miss.

I only hope that I can remember all that you taught me, both in science & in life.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed